In its 2024 Democracy Index, The Economist pinpointed one key faller on the global democratic stage: Bangladesh. Notably, Bangladesh was also the first country to hold an election in 2024, with its general election taking place on 7 January 2024. I was present to witness the final stages of this election as an Election Monitor. While I observed robust electoral processes on the ground, the fault lines were evident, with opposition parties boycotting the election, leading to a diminished participatory mandate.

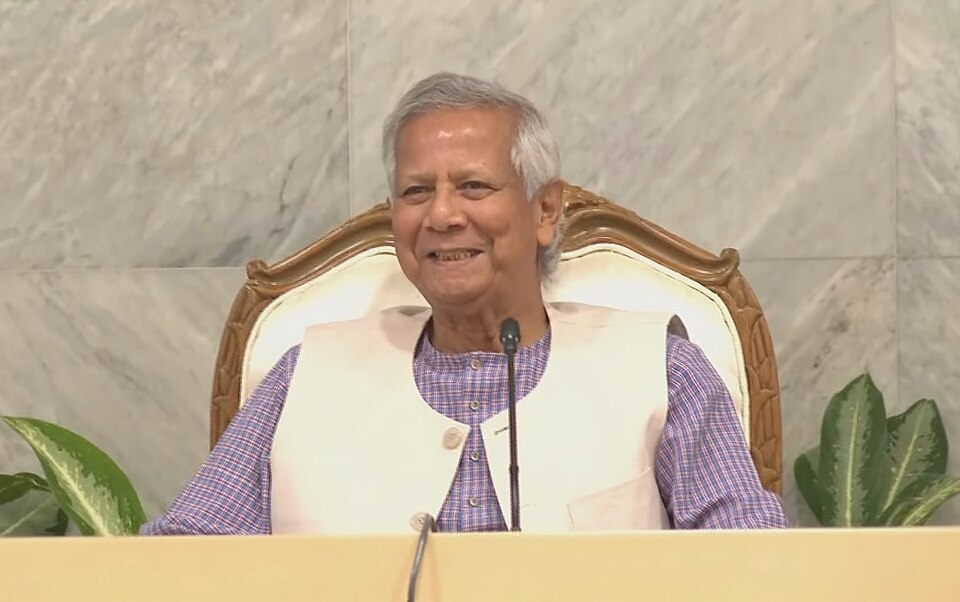

Following the ousting of its long-serving Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who was forced to flee the country amid widespread student protests that were triggered by proposed changes to public sector quotas but soon grew into a mass non-cooperation movement against the ruling government – Bangladesh appointed—but did not elect—Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus as its interim leader, tasked with establishing stability after a tumultuous summer of civil unrest.

Under the Constitution of Bangladesh, the resignation of a Prime Minister is not a matter of personal discretion or political expediency—it is a formal constitutional act requiring a written submission to the President. Yet, following Sheikh Hasina’s abrupt departure from office on 5 August 2024, serious doubts have emerged as to whether this fundamental requirement was met.

President Mohammed Shahabuddin has since stated that no written resignation was ever received. If accurate, this raises troubling questions about the constitutional basis upon which power was transferred to the current interim administration.

With the appointment of Muhammad Yunus’s interim government, Bangladesh finds itself in an unprecedented constitutional situation where only the President remains in office as a legitimate constitutional authority. Under Bangladesh’s parliamentary system, established in 1991 following a return to democratic rule, the presidency was transformed from an executive role to a largely ceremonial position elected by Parliament.

Despite this normally ceremonial role, the constitution provides the President with enhanced executive authority after Parliament is dissolved. This critical constitutional provision becomes especially significant in the current context, as President Mohammed Shahabuddin—elected unopposed in February 2023 and who took office in April 2023 for a five-year term—now stands as the sole constitutionally legitimate office holder in Bangladesh’s government apparatus.

The presence of a constitutionally appointed President while an extra-constitutional interim government exercises de facto control creates a fundamental tension in Bangladesh’s governance structure. President Shahabuddin’s constitutional mandate continues regardless of parliamentary status, as the constitution specifies that a president continues to hold office even after their five-year term expires until a successor is elected. This creates a paradoxical situation where the interim government operates without elected constitutional legitimacy while the ceremonial head of state retains constitutional authority but limited practical power to resolve the current democratic impasse.

Bangladesh has been a democracy since 1971, when it gained independence from Pakistan. Its first elected leader was Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who led the Awami League to victory in Pakistan’s first general election, before becoming Bangladesh’s first President and the architect of its secular constitution. Tragically, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated along with most of his family members in the early hours of 15 August 1975 by a group of Bangladesh Army personnel who invaded his residence as part of a coup d’état. This devastating event marked the beginning of a sad history of political violence that has periodically scarred Bangladesh’s democratic journey.

Now, Bangladesh stands at a precipice, guided for the first time in its history by an administration with no constitutional basis, no experience of governance, and no true political mandate. Much of Yunus’ advisory council is composed of individuals with little to no political experience. According to Supreme Court lawyer Shahdeen Malik, there has been no provision within the Bangladeshi constitution for the formation of an interim government since the 15th Amendment was repealed in 2011. In practice, this means there is no legal obligation to hold elections.

In December 2024, the Bangladesh High Court struck down a key section of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution—which had previously abolished the non-party caretaker government system. However, the court was careful to clarify that the current Yunus-led interim administration does not fall under the scope of this ruling, raising further questions about the legal and constitutional basis of the present government.

Since taking office, Yunus has proposed a sweeping programme of reforms, from the judiciary to the press to the electoral system itself, declaring that elections would not be held until these reforms are fully implemented. Yet, after a year in power, the interim government had failed to define its reform agenda or set a clear roadmap for elections until the announcement from Yunus that new elections should take place in February 2026. Meanwhile, the country has descended into lawlessness, with increasing reports of political and religious violence targeting ordinary citizens – a troubling echo of the political violence that has periodically destabilized the country since its founding.

Among the administration’s most vocal critics is the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which has called for a return to elected government since its first protest rally against Yunus’ rule on 8 November. The BNP had raised concerns over the uncertain election timetable, which reportedly ranged from December 2025 to June 2026, with some within the party alleging that reforms are being used as a pretext to delay elections, and has welcomed the move for February elections.

Bangladesh’s political parties remain sharply divided over the newly announced election timeframe, with figures such as Samantha Sharmin of the National Citizen Party warning that it is “difficult to even imagine a fair and acceptable election under the current context.”

Tensions escalated on 10 May 2025, when the interim government formally banned the Awami League under the Anti-Terrorism Act. The move, reportedly supported by the National Citizen Party (NCP)—a youth organisation aligned with the interim authorities—has drawn sharp criticism, with observers such as India warning it could deepen civil-military tensions and erode prospects for inclusive democratic dialogue.

In a recent global update to the 59th Human Rights Council, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk expressed concern over Bangladesh’s recent legislative changes enabling the banning of political parties and related activities. He warned that such measures “unduly restrict” fundamental freedoms, including the rights to association, expression, and peaceful assembly.

This situation underscores two essential points:

First, the urgent need for free, fair, and participatory elections, without exclusion of legitimate political forces.

Second, the question of mandate—whether an unelected government has the authority to impose structural and constitutional reforms that it itself will not be accountable for implementing.

As BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir has argued: “Only an elected government—accountable to the people and committed to justice and good governance—can successfully carry out meaningful reforms.”

History offers stark lessons. Ethiopia’s celebrated democratic transition under Abiy Ahmed quickly unravelled after election delays in 2020 triggered civil war in the north of the country. Bangladesh must not follow the same path.

Now that an election timeframe has been announced, the Yunus administration must be held accountable for ensuring that the vote is genuinely free, fair, and inclusive. The focus must shift from merely announcing a date to guaranteeing a credible democratic process.

A European Union pre-election observation team is set to visit Bangladesh in mid-September to assess the electoral environment and evaluate the Election Commission’s readiness for the upcoming 13th parliamentary election. Their assessment will play a crucial role in shaping international perceptions of the credibility and inclusiveness of the electoral process.

Moreover, the international community must not look away. The United Nations should be urgently pressed to conduct an independent investigation into the situation in Bangladesh—assessing the risks of potential repression, the dangers of the country falling further into turmoil, and the wider implications for regional security.

It is important to note that the international community has already begun documenting abuses. The UN Human Rights Office released a comprehensive, in-depth report on the human rights violations and abuses related to the protests that took place in Bangladesh last year. This thorough investigation drew on over 250 interviews with victims, witnesses, medical professionals, and senior officials, supplemented by individual pieces of digital information. The UN team also received thousands of submissions from individuals in Bangladesh, creating a substantial body of evidence documenting the situation.

However, this existing UN investigation, while valuable, only covers the period of protests that led to the interim government’s formation. There is an urgent need for further UN-led documentation and investigation into the alleged human rights abuses that have been reported since the interim government took power. These more recent reports of violence and rights violations require the same level of scrutiny and international attention to ensure accountability and protect Bangladesh’s citizens during this precarious political transition.

An unelected administration that clings to power, marginalises political opponents, and incites societal divisions betrays the democratic tradition upon which Bangladesh was founded. Without urgent international engagement, there is a grave risk that a once-promising democracy could slide into deeper instability and civil strife.