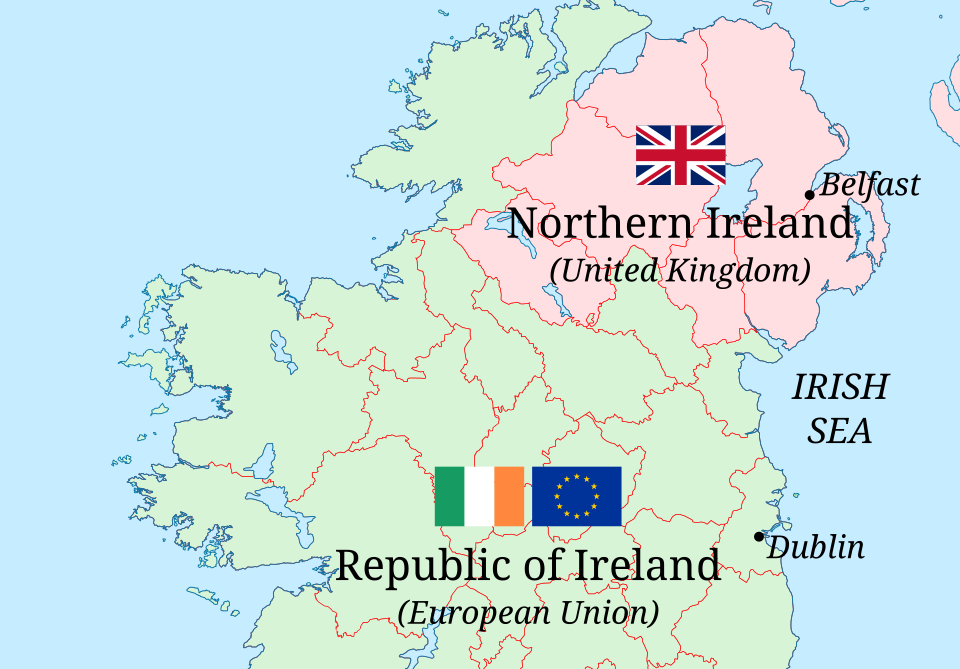

Northern Ireland has developed a model that is hugely underestimated by its citizens. It has managed to bring together two sides that lived in such a state of division, both politically and physically, that they found themselves mired in a 30 year conflict which cost 3,720 people their lives. Although this number is a fraction of what is being seen in many other conflicts today (with 1400 killed in one month in Bangladesh, the 60,000 Rohingya people displaced from Myanmar, or the conflict in Gaza claiming almost 65,000), the ongoing peace and reduction of sectarian violence in Northern Ireland, as well as the collaboration of all parties to deliver stable governance is almost singular.

Understanding the Climate

It has been 27 years since the signing of the Belfast Agreement, more commonly known as the Good Friday Agreement. Although this was not the first Agreement seeking to bring together either side of the religious division in Northern Ireland, it was the most widely supported. This Agreement established a system of democratic governance based on a form of proportional representation called Single Transferable Vote (STV) that promised ‘true power-sharing’ to the people of Northern Ireland.

For decades this region had experienced division between the largely Catholic ‘Nationalists’ or more extreme ‘Republicans’ and mostly Protestant ‘Unionists’ or similarly more extreme ‘Loyalists’, with both Republicans and Loyalists often using violence to progress their political aims. In its most simple form, the former sought to oust British rule and the latter to ensure its continuance.

Prior to 1998, there was a period of disarming, with paramilitary groups decommissioning weapons in order to demonstrate commitment to the Peace Process. This ultimately resulted in negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement and the establishment of the Northern Ireland Assembly.

The subsequent elections embedded the key engineers of the Agreement as the two largest parties; the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) led by David Trimble and the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) led by John Hume and the leaders, following their Nobel Peace Prize, became First and Deputy First Ministers respectively.

Despite religion being one of the primary factors influencing the Peace Process in Northern Ireland, it has been the case that Nationalist and Republican parties have been predominantly left wing inclined and Unionist / Loyalist favour more conservative and right-wing policies ( which of course presents a conundrum for right-wing Nationalists or left-leaning Unionists). The UUP and SDLP were both seen as the more centralised parties for Unionists and Nationalists and in the years following the Good Friday Agreement have both experienced significant declines in their popularity.

In 1998, Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) refused to take part in negotiations with Sinn Féin and Loyalist parties. In the years since, Sinn Féin has distanced itself from its connections to Republican groups, such as the IRA and grown in popularity, replacing the SDLP as the largest Nationalist Party in 2003, becoming the most popular party overall in 2022.

In a similar shift from the centre, the DUP replaced the UUP as the largest Unionist Party in 2003. This led to a new agreement, expanding on the Good Friday Agreement to be negotiated. The St Andrews Agreement was put in place in 2006. This cemented power-sharing and established more safeguards portioning out executive responsibilities using the d’Hondt System.

Has it worked?

In the 27 years since the Good Friday Agreement and 19 years since the St Andrews Agreement, Northern Ireland has experienced a continued reduction in sectarian violence. Simultaneously, voting patterns have moved drastically away from the centre, favouring often controversial parties regardless of past connections or ongoing financial and criminal scandals. There also remains a fairly widespread habit of tactical voting practices, that see voters cynically aligning to the perceived ‘stronger’ party, rather than the party closest to their political opinions, in order to ‘keep the other side out’.

The Northern Ireland Assembly has been suspended six times since 1998, due to deadlocks or an inability to come to a power-sharing agreement. Prior to the DUP and Sinn Féin becoming the largest parties, the longest suspension was just over 100 days, however, since their rise to prominence there have been two suspensions over three years and one just under two years. During periods of suspension, decision making reverts to the Northern Ireland Office of the UK Government and rests in the hands of Senior Civil Servants and Members of Parliament not elected by the people of Northern Ireland.

The electoral system in Northern Ireland was selected specifically to ensure the greatest proportion of representation at every level of government. Thus ensuring neither side would be able to obtain a monopoly of control over any responsibility or power. Largely this has been effective and has shifted Northern Ireland into a more tolerant and modern society. Although the rule of power-sharing has its drawbacks, mostly through a single party’s ability to halt all governance through deadlocks, the majority has found a route to govern. Northern Ireland is likely to remain a deeply divided society for generations to come, but in a single generation it has moved away from violence and blatant sectarianism, despite having almost no experience of direct democracy since the heavily flawed Parliament of Northern Ireland (1921-1972). The people now hold their elected representatives to a high standard and view their ability to elect a representative to local government as a right, even if at times the options may not reflect their political inclinations. The choice between voting influenced on sectarian boundaries, rather than mandates, sadly remains prevalent.

Has Northern Ireland cracked the code for Democracy in a Deeply Divided Society? Probably not. There remains a concerning habit for a single party to halt all government and pull the Northern Ireland Assembly into a deadlock, as seen during the Brexit negotiations. The entire local governmental system relies entirely on full collaboration, and when one party refuses to collaborate governance reverts to Westminster, meaning a democratic deficit for the people actually living there. However, these deadlocks, while irritating, have not resulted in a return to the violence since in the 1970s and 1980s and so the current system cannot be regarded as completely unsuccessful, whatever its flaws. As Northern Ireland approaches thirty years of peace, it may be time to consider eliminating the power that one party can exercise over the entire Assembly by safeguarding against the repetition of prolonged deadlocks. This failsafe functionality was useful to establish the democratic infrastructure but in recent years has eroded public confidence and curtailed electoral mandates.

Can other deeply divided societies learn from this model?

Any success and progress Northern Ireland has experienced has been a prolonged evolution and the result of significant investment from a wide range of stakeholders committed to de-escalating tensions, decommissioning weapons, bringing together all parties to negotiate a peace and establishing genuine democratic institutions. Northern Ireland’s geographical location and connection as part of the UK brought in regular focus from some of the most powerful Western countries as well as their investment, which other countries experiencing conflict may not benefit from. In the 1990s, the appetite for Peace was at its zenith both within and outside Northern Ireland. That does not appear to be the case with many of the most bitter conflicts fueled by religious or ethnic differences ongoing today. It is my hope that Northern Ireland may move from a dark and dangerous corner of an island, known only for its Troubles, into a symbol of hope and peaceful resolution that may become a blueprint for democracy in regions of religious and ethnic conflicts.Northern Ireland has developed a model of democracy, which although flawed, has established and maintained a peaceful resolution to conflict and violence that countries facing similar divisions would do well to learn and be inspired by.

Claire Fawcett,Board Member of the International Association for Democracy (IAD)

Mail: press@iad.ngo